Number of Canadians donating to NGOs rising

Canada’s government recently increased its foreign aid budget.

Now Canadian NGOs want to show the ruling Liberal Party they made a good decision—and that

lots of Canadians support it.

But how to do that?

Plans are underway for postcard, e-mail and letter writing

campaigns, among other things. The hope is that tens of thousands of

Canadians will show the government they care about people in need in the

developing world.

And also that Canada should keep moving in this positive

direction.

But what if it could be shown that lots of Canadians already do care? Not tens of thousands, or even hundreds of thousands, but millions? And that this support is increasing?

What am I talking about? Giving money.

Now, I've met some people who think giving money is the least important way people

can show commitment to the cause.

Letters, MP visits, e-mails, attending events—those are

considered to be far superior.

As a fundraiser, I know that isn’t true. Writing letters and e-mails is important, but so is making a donation.

Giving money to a charity is a

serious and deliberate act. People don’t give it away easily.

And when you consider the many other options people have for

spending their hard-earned dollars, making a donation—especially a larger amount—is a significant

expression of commitment to a cause.

But if giving money is another important way to measure engagement, how much is being given by Canadians to international causes? And is it growing or decreasing?

But if giving money is another important way to measure engagement, how much is being given by Canadians to international causes? And is it growing or decreasing?

That’s what I set to find out. I started by searching online.

The only thing I could find was a 2002 a report titled “An Analysis

of Canadian Philanthropic Support for International Development and Relief.” It was commissioned

by the Aga Khan Foundation of Canada and published by the Canadian Centre for

Philanthropy—now Imagine

Canada.

That report, based on the 2000 Statistics

Canada National Survey of Giving, Volunteering, and Participating, showed

that 5% percent of Canadian donors—about 1.2 million people—supported

international causes that year, giving about 3.4% of total donations to NGOs.

The report noted that “Canadians

provide only modest philanthropic support for international development and

relief efforts.”

However, it went to say there “appears

to have been substantial growth in the amount of donations provided to

international organizations between 1997 and 2000, which far surpassed the

overall growth in charitable donations.”

While that was

a hopeful sign, data from 2000 wasn’t going to cut it. So I contacted David Lasby, Director of Research and Evaluation for Imagine Canada, and one of the

authors of the 2002 report.

I

asked him if Imagine Canada had any updated data on giving for international relief

and development.

He said no; they didn’t.

But,

to my surprise—and delight—David took this on as a challenge.

He

crunched the numbers for giving to international causes in 2013 (the most recent year for which data was available), using information from that year's National Survey of Giving, Volunteering and Participating.

And

what did he find?

“Briefly,

things have changed quite a bit somewhat since the earlier numbers,” he reported

back to me.

“As

of 2013, about 12.8% of donors, or 10.5% of Canadians, donated to International

development and relief organizations.”

Collectively,

he added “organizations working in this area presently account for about 10% of

the total value of donations to all organizations.”

According to Lasby, this totaled about $1.3

billion donated to international NGOs in 2013.

In terms of number of donors, Lasby says his research shows that about 3.1

million Canadians donated that year to help those in need in the developing world—an

increase of almost 1.2 million people over 2000.

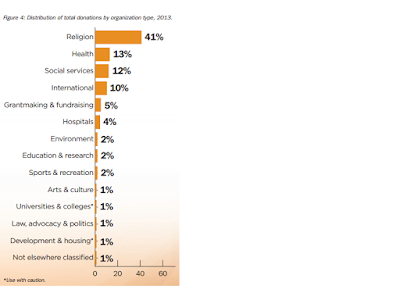

According to a recent report from Imagine Canada and the Rideau Hall Foundation’s latest report, Thirty

Years of Giving in Canada, giving to international relief and development

is now the fourth most popular cause for Canadians to give to, after religion

(41%), health (13%) and social services (12%).

Or, as that report puts it: "Giving to international causes is increasing, both in terms of the amounts donated and the number of Canadians donating."

Or, as that report puts it: "Giving to international causes is increasing, both in terms of the amounts donated and the number of Canadians donating."

(Above graphic from Imagine Canada; see also this table from Statistics Canada for the donor rate and amounts donated to different organizations in 2013.)

But was that just a blip? Maybe there was a big disaster in 2013 that skewed the numbers.

But was that just a blip? Maybe there was a big disaster in 2013 that skewed the numbers.

As it turns out, there was.

That was the year of Typhoon Haiyan in The Philippines, a huge

disaster that dominated the news.

Canadians donated over $85 million to international NGOs that

year to help victims of that disaster. (Spurred on by a government match of 1:1.)

Despite this, Lasby says the data shows there has been a steady

climb in donations for relief and development since 2000.

“Looking at the intervening surveys, the increases in percentage

of total donation value have been quite consistent,” he says.

His comments made me wonder; could his information be supported

by an increase in donations to Canadian NGOs?

With David’s help, I checked out giving to some of the country’s

largest and best-known NGOs.

It turns out the answer is yes.

Of the nine major NGOs I looked at, all except one saw their giving increase between 2003 to 2016-17. Some of them increased quite a lot. (See list below.)

So: What does this mean?

When it comes to demonstrating to the government that Canadians care about foreign aid and international development, maybe NGOs have been selling themselves short.

Perhaps there are many more people engaged in our mission than we

thought—people who care whether Canada’s aid budget goes up or down.

So maybe instead of only counting postcards, petitions and e-mails—all

important things—we can also show politicians our fundraising totals.

That might also tell a very important tale.

Examples of giving to NGOs,

2003-16 (individual donations)

Save the Children: 2003, $3.3 million; 2016, $7.1 million.

Oxfam Canada: 2003, $5.3 million; 2017, $7.1 million.

Plan Canada: 2003, $44.7 million; 2017, $93 million.

Red Cross: 2003, $25.8 million; 2017, $224 million.

Islamic Relief: 2007 (first year of operation), $40,765; 2016,

$18.5 million.

World Vision: 2003, $145.1 million; 2016, $348.7 million.

Samaritan’s Purse: 2003, $8.4 million; 2016, $30 million.

Compassion Canada: 2003, $10.5 million; 2017, $61.2 million.

CARE: 2003, $5.4 million; 2017, $5.4 million.